Looking Through the (Murky) Looking Glass

OVERVIEW

Commercial real estate weathered a difficult year in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. Physical distancing changed the way we inhabit and interact with physical space, and the cumulative effects of the virus have made the demand for many types of space go down, leaving markets reeling and “in recovery mode.”Despite its challenges, 2021 was a year of transformation for the industry. The year ahead is likely to see further improvement in our markets as the economy continues to recover. Here, the research team at SVN fixes its eye on the horizon, offering predictions and guidance on the year ahead for commercial real estate trends.

We offer three trends likely to persist through 2022:

- The suburban office renaissance is still in its early stages.

- Apartment cap rates will see upward pressure.

- The labor market shortage is not going away.

SURBURBAN OFFICE

Commence the Renaissance

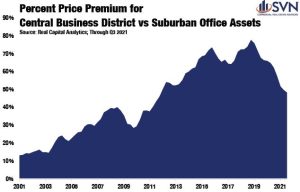

Picture this: The date is January 2001. You are in the market for acquiring a new office location for your company’s headquarters. You can either choose a suburban office location and pay $132 per square foot or pay a modest 12.9% premium at $149 per square foot to bring your office into the central business district (CBD).

Now, fast-forward to 2018. Once again, your company is on the move, and you are tasked with heading up the re-location selection process. Your options are: 1.) Select a suburban office location for $211 per square foot, or 2.) Pay a hefty 77.3% premium to bring the office to the city center at $374 per square foot.

This is a hypothetical situation, of course, but it demonstrates a real truth: the comparative value between suburban and CBD-located office space dramatically changed in less than two decades’ time. Even before the pandemic (starting in early 2019), the long-dated trend of an increasing premium for CBD-located office assets had started to reverse. Of course, once the pandemic hit and downtown city center emptied, the price convergence accelerated as suburban assets have seen record levels of price growth while CBD assets have yet to recover their pre-pandemic highs. Through Q3, the average price premium for CBD office assets over suburban assets is down 48%.

With an eye on the horizon, there are several reasons to believe that the premium between CBD and suburban assets will continue to gall. The first is simply arbitrage. Surely CBD assets deserve a price premium above non centrally located suburban assets. However, a 48% premium remains above the 20-year average (44%) and well above where it sat to start the last commercial real estate cycle (29%), suggesting that values may converge more yet.

Also consider that across all age groups and education levels, Americans are showing an increased preference for suburban housing option over walkable, urban options. according to Pew Research Center.

Also consider that across all age groups and education levels, Americans are showing an increased preference for suburban housing option over walkable, urban options. according to Pew Research Center.

Couple these above findings with the fact that the emergence of work from home has serious staying power beyond the end of the pandemic- a development that could favor suburban office assets as workers prove less willing to tolerate long commutes. According to the Owl Lab’s 2021 State of Remote Work Report, 70% of respondents in its survey indicate a desire for a remote or hybrid setup post-pandemic. Moreover, 48% of respondents reported that if they were not given the option to work remotely after the pandemic, they would seek a new job. If workers are structurally less tied to urban offices post-pandemic, it presents an opportunity for suburban providers. According to recent reporting from the New York Times, several co-working providers have turned their attention to the suburbs, betting on rising aggregate demand for flexible space away from city center.

Altogether, suburban office assets are coming off a strong year where asset prices have surged ( up 15.6% year-over-year through October). Even still, suburban office assets have the wind at their back heading into 2022 with what appears to be a multi-year renaissance ahead.

Apartment Cap Rates Will Do the Unthinkable: Rise

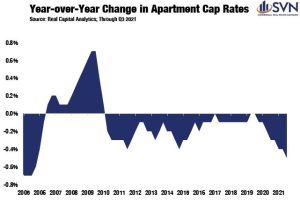

If death and taxes are the first two certainties of life, over more than the past decade, declining cap rates across the multifamily sector was surely a close third. According to a Chandan Economics analysis of Real Capital Analytics data, apartment cap rates started to compress post-Great Financial Crisis on a year-over-year basis beginning in Q2 2010. In the 46 elapsed quarters between then and Q3 2021, apartment cap rates fell a total of 43 times. Nevertheless, there is growing evidence to think that 2022 may be the year that apartment cap rates start to reverse from their all-time lows-even if only marginally.

Understandably, rising cap rates are not something that lands softly on the ears of operators. However, here, the why is more important than the what, and rising apartment caprates may be good news for operators this time around-even for those currently controlling assets.

A key feature of this forecast is that rent inflation will continue to surge in 2022. Moreover, the team at Chandan Economic s expects that rent inflation will exceed the pace of rising asset valuations. Historically, there is a time lag between rising asset valuations and rent inflation, meaning that if 2021 was a banner year for asset prices, rents could see a catch-up period in 2022. According to RealPage Analytics, this rent surge is already well underway, and momentum is holding up as we reach the end of the calendar year. Functionally, if rent inflation does outpace asset value inflation in the year ahead, there would be more net operating income for every dollar of asset value, causing upward pressure on cap rates.

s expects that rent inflation will exceed the pace of rising asset valuations. Historically, there is a time lag between rising asset valuations and rent inflation, meaning that if 2021 was a banner year for asset prices, rents could see a catch-up period in 2022. According to RealPage Analytics, this rent surge is already well underway, and momentum is holding up as we reach the end of the calendar year. Functionally, if rent inflation does outpace asset value inflation in the year ahead, there would be more net operating income for every dollar of asset value, causing upward pressure on cap rates.

Beyond strengthening net operating incomes, the Federal Reserve is the other macroeconomic elephant in the room that will have the power to move capital markets globally, including domestic cap rates.

As of December 2021, implied probabilities on options contracts indicate that the market expects at least one rate-hike by mid-2022. Going further, most market participants expect the fed raising rates at least three times by the end of 2022. If market interest rates are on their way up, minimum investor yields on real estate assets will directionally follow.

Certainly, the reliability of fundamentals in the US renal housing sector will continue to attract capital, especially from investors who are looking for an assets that frequently resets its cashflows, offering inflation risk protection. The incoming flow of new buyers into the multifamily space seeking hedges on inflation should offer a counterweight, applying downward pressure on cap rates. Nevertheless, the balance of factors in the year ahead favors more upside pressure on cap rates than down.

Tight Labor Markets: Not New, Not Going Away

As you’ve probably heard, nobody wants to work anymore. Of course, while this broad stroke assessment is a response to a very real labor shortage, the prognosis is sorely misguided. There were still more than five

million people out of work collecting unemployment benefits in early 2021- a considerable improvement from the 23 million recorded in spring 202, though still nearly three times higher than pre-pandemic normality. It was around this time that most “nobody wants to work anymore” narratives got their beginnings, and at least there was some data to point to that suggested workers were taking their time coming off the sidelines. Now, with continuing unemployment benefits falling below 2 million claims through the end of November, the theory has lost some of the meat on the bone.

million people out of work collecting unemployment benefits in early 2021- a considerable improvement from the 23 million recorded in spring 202, though still nearly three times higher than pre-pandemic normality. It was around this time that most “nobody wants to work anymore” narratives got their beginnings, and at least there was some data to point to that suggested workers were taking their time coming off the sidelines. Now, with continuing unemployment benefits falling below 2 million claims through the end of November, the theory has lost some of the meat on the bone.

Nevertheless, labor markets remain exceptionally tight, and hiring managers are competing for talent in ways not seen in generations. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, wages for production and nonsupervisory employees are up by 5.9% in November from a year earlier- the highest rate since 1982.

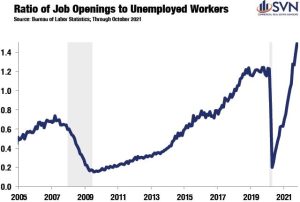

However, what is often missed is that the labor market gradually tightened since the end of The Great Recession, and pressures were already reaching a boiling point before the pandemic. Before the GFC, a time that labor markets were also very tight, there were 0.7 job opening for every unemployed worker. Fast forward to the full year before the pandemic, and the ratio of opening to unemployed workers plateaued at a significantly higher 1.2. Now, as of the October, 2021 Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (released in December), there are 1.5 job openings for every person who is classified as unemployed- a new and jarring all-time high.

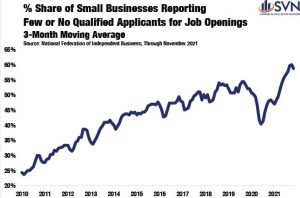

Another piece of the puzzle to consider is finding workers- they have even a tougher time finding qualified workers. According to the National Federation of Independent Business, nearly 60% of small business owners report receiving few or no qualified applicants for available positions, a pattern that continued to get worse over the past decade. Altogether, these data paint a picture of a labor shortage that is structural and unlikely to correct itself over the short term.

What a persistently tight labor market means for real estate is twofold. First, and the most obvious, a scarcity of availability of workers could leave critical parts of the commercial real estate sector understaffed. Most concerningly, this is already observable in the construction industry. As of September 2021 NMHC Construction Survey, 88% of respondents reported being impacted by labor availability. Secondly, tight labor markets are transmissions for increases in wage inflation and general inflation. Sustained high inflation would have implications for both rents and interest rates across all commercial real estate sectors.

And We’re Off

While the scope of uncertainty has undoubtedly shrunk over the past year, it is not to say that we have returned to normal. At the time of this writing, the omicron variant appears to be more bark than bite, but its rapid spread and ability to evade established immune responses highlights a continued risk heading into 2022, especially if new variants are detected that are more bite than bark.

The interconnection between supply chain shortages, labor shortages, and inflation are all contributing to a unique moment in economic history- one that is surely giving central bankers cause for restless nights.

All else equal, commercial real estate remains entrenched in a period of significant change. With shifting patterns of where people live, how they shop, and how they work, updates to how we use our built environments are a natural evolution.

May this piece serve you as a theoretical model in the year ahead, but head the timeless advice of George Box in the process: “all models are wrong, but some are useful.”

Prepared by: SVN Research & Chandon Economics